The “Frankfurt Kitchen” is an important document of cultural history for the transfer of industrial, rationalized work processes to the sphere of the private household. This is a central characteristic of modern architecture and everyday culture in the 1920s.

The Viennese architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky designed the kitchen in 1926 as a standard prototype. Some 10,000 such kitchens were realized in numerous variants in the Frankfurt estates. Schütte-Lihotzky was commissioned by the Frankfurt building inspector Ernst May, who was both the architectural designer and the local administrator responsible for the “New Frankfurt” of the 1920s. In view of the scarcity of rental housing in Frankfurt after the First World War, this building programme was intended to produce cheap, efficient housing with an economical use of use space and simple, economical furnishings for a growing population. The housing estate building programme, supported mainly by the SPD, was politically motivated and aimed at providing the technical and hygienic standards of the day — running water, gas and electricity — to the lower classes. The programme was publicized through a modern campaign. As part of that campaign, the kitchen was presented and well received at the Frankfurt spring fair of 1927.

The development of a standardized modular system made it possible to reduce the floor area required, and also permitted mass production which lowered costs further.

The “Frankfurt Kitchen” was widely marketed and became the model for the fitted kitchen of today. There is not just one Frankfurt Kitchen, however. The model underwent several changes during the period in which it was realized in a number of Frankfurt estates until 1930.

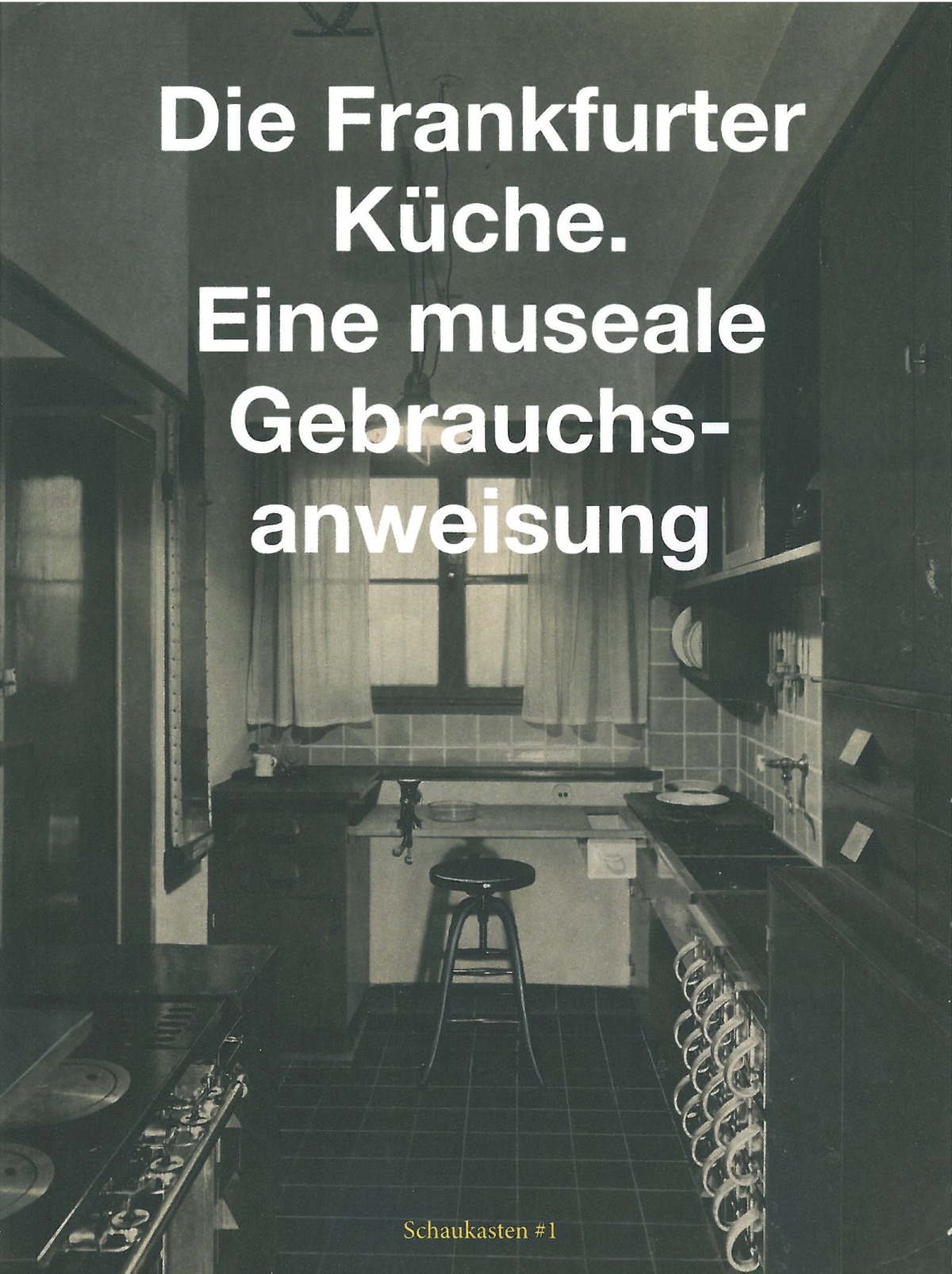

The “Frankfurt Kitchen” was designed to be efficient and functional, modeled after railway dining car kitchens, and planned based on taylorized work processes. It was intended to be used as a “cooking workroom”, and divided from the sitting room by a sliding door.

The “Frankfurt Kitchen” specimen in the display collection of the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge was taken from a two-family terrace house at Heidenfeld 24 in the Römerstadt estate, built in 1927-28. The kitchens in the Römerstadt estate lacked the sliding door and the hay box that is present in other Frankfurt Kitchens, and was equipped with a combination coal/electric cooker. The kitchen cabinets were originally painted blue-green, and were repainted in a cream color during its years of use. The kitchen is exhibited in its unrestored state to show the authentic signs of use and modification. Paint has been removed from the fittings, however, and some missing parts have been replaced.

The ensemble is an ideal addition to the Museum’s collection because the Frankfurt Kitchen illustrates key principles of the 1920s: objectivity, functionalism, and above all, standardization. The concept of standardization was connected not only with production techniques, but also reflected the ideological position of the Bauhaus and Werkbund activists, who saw the uniform design of everyday objects as a contribution towards leveling the differences between classes. The artistic design of the standardized object served to refine it and to ensure that the right form was definitive.

The “Frankfurt Kitchen” was one of the models propagated by the Werkbund and the Bauhaus for the “New Life” of the “New Man”, an idea that was widely popular in the 1920s. These visions involve a renunciation of historically determined elements of identity. Bruno Taut, in his book Die Neue Wohnung (“The New Home”), rejects the presence of mementos and any kind of “historic junk”. Erna Meyer, the academic housekeeping expert of the 1920s and 1930s, wrote: “Now it’s all or nothing: New Man needs a new skin!” (Wohnungsbau und Hausführung, 1927, 89).

A “planned order” was to replace the “senseless chaos” of the world. The notion of a regularly constructed reality corresponds to the principles of functionalism and rationality conditioned by industrial production processes. Both objects and people were to conform to these principles.

The consequences of these reformative initiatives, especially in housing estate architecture, were criticized in debates on socially supported housing in the 1970s and 1980s. The image of women that is evident in the Frankfurt Kitchen concept must also be viewed critically. A purely functional working kitchen was intended to make housework easier, but without questioning the gendered division of labour.

Alongside the actual kitchen exhibited in the museum, visitors can examine an audiovisual installation based on historic photos and films, a 1985 interview with the designing architect, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, and the findings of two researchers who spent years studying the Frankfurt Kitchen. Astrid Debus-Steinberg of the Stuttgart Society for the Conservation of Art and Historic Monuments (Stuttgarter Gesellschaft für Kunst und Denkmalpflege) has preserved, collected and systematically researched and many Frankfurt kitchens since the late 1980s. The cultural historian Dr. Joachim Krausse, together with the architectural theorist Jonas Geist, made a documentary film in the 1980s as an archaeological study of the discrepancies between the idea and the reality of the New Frankfurt.