First Part of the Exhibition Series “111/99”

The Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge is showing a sequence of four exhibitions entitled 111/99. Questioning the Modernist Design Vocabulary in the context of the Bauhaus year since November 2018 to the end of 2019.

Twelve years separate the 1907 founding of the Deutscher Werkbund reform movement and the 1919 founding of the styledefining Bauhaus Art School – the Deutscher Werkbund turned 111 in the year 2018, and the Bauhaus turned 99. Taking up the anniversaries as a play on numbers, the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge interrogates the programmatic overlap between the two institutions in the development of a modernist design idiom.

Why did certain features develop into trade marks of modernity, and why do they remain fixed to this day, despite any and all critical thinking: materials like glass, steel, and concrete; terms like objectivity, unadorned form and functionality; the colors white, black, and grey? How did the Werkbund and Bauhaus Lebensreform concept that was influenced by social, political, and economic debates get reduced to the rigid straight forwardness of a purely aesthetic recipe for design or book of patterns?

These questions will be discussed in a sequence of three exhibitions:

COMMERCIAL DESIGN INSTEAD OF APPLIED ART?

Since November 23, 2018 – March 11, 2019

UNIQUE PIECE OR MASS PRODUCT?

April 04, 2019 – August 19, 2019

DECORATION QUA TRESPASS?

October 11, 2019 – February 10, 2020

Opening: October 10, 2019 at 7 pm

Commercial Design instead of Applied Art?

Duration: 23 November 2018 – extended until March 11, 2019

In 1909 – just two years after the 1907 founding of the Deutscher Werkbund – the first Werkbund Museum came into being in Hagen: the Deutsches Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe (German Museum for Art in Trade and Industry, aka DM).

By the time of its dissolution in the early 1920’s following the death of its founder, entrepreneur and Werkbund member Karl Ernst Osthaus, the museum had evolved into an effective promoter of the modern design of everyday goods with its unconventional structure oriented on circulation and networking.

The museum organized traveling exhibitions on contemporary product culture, advised entrepreneurs, trade, as well as designers, and organized lectures and training programs on modern design. Beyond that, the DM had structures photographically documented and announced display window competitions. In collaboration with the F.W. Ruhfus Publishing House in Dortmund, it published a series called “Monographien Deutscher Reklamekünstler” (Monographies on German Commercial Artists).

Via its “Exhibition Central,” the DM lent up to 26 exhibitions with exhibits and presentation elements to museums, art and trade associations, libraries, trade colleges, and similar educational institutions in Germany and abroad during its most active period in 1913/14. The exhibitions it lent clearly demonstrate the broad museum-quality spectrum related to contemporary production: extending from consumer graphics over rugs and floor coverings, textile art, glass painting, metals, modern architecture, exemplary teaching aids, weaving, ceramics, and glass, to stone, wood, and leathers.

Ultimately, the DM’s collection not only united the most important artists of the Deutscher Werkbund and therefore also early modernity, it also illustrates the contradictory tendencies within the applied arts movement prior to the First World War.

The first Werkbund Museum working in the spirit of a modernization agency discontinued its work concurrently with the founding of the Bauhaus in Weimar.

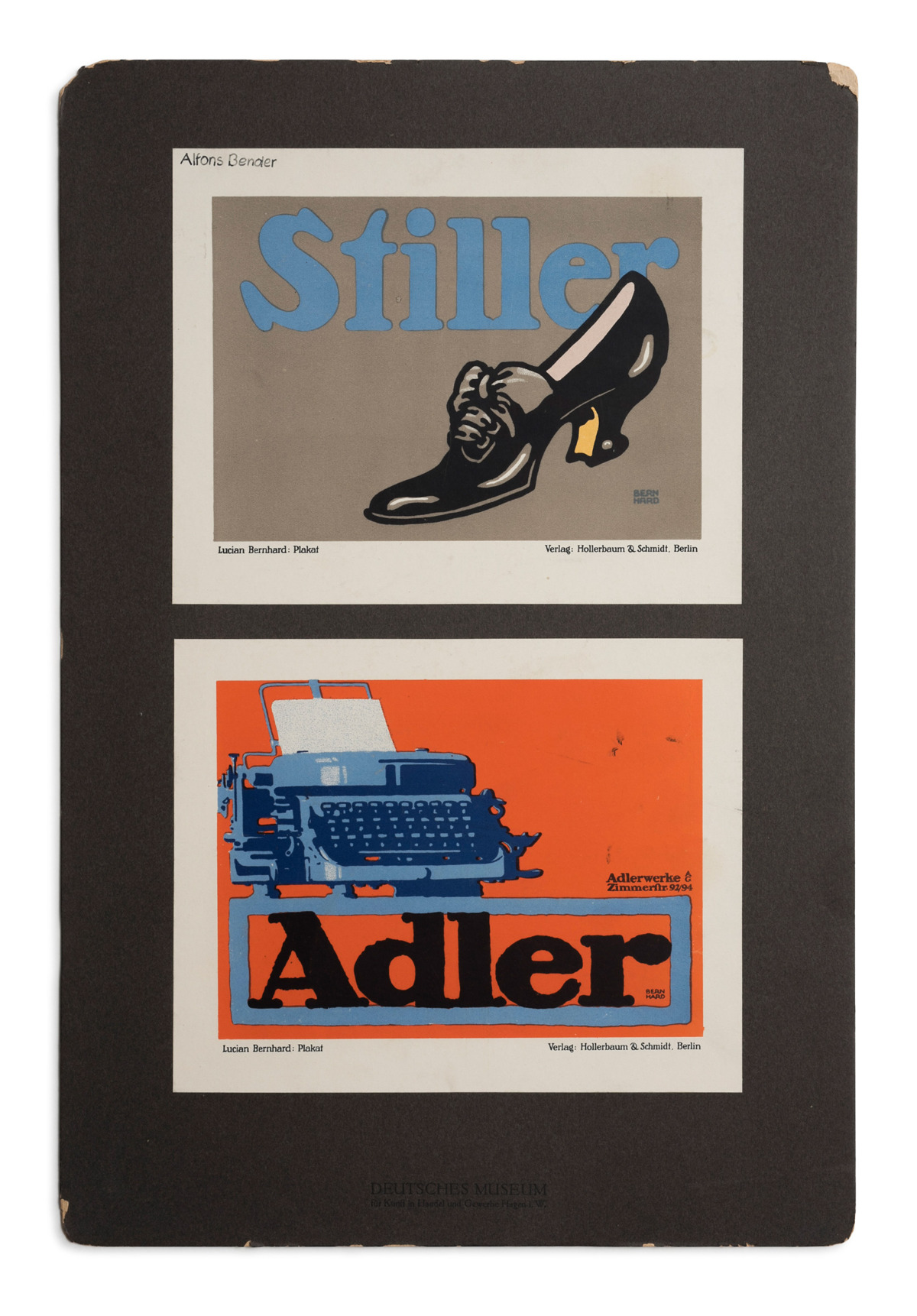

In the exhibition “Commercial Design Instead of Applied Art?,” the Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge presents a recently acquired stock of commercial graphic design from the context of the Deutsches Museum für Kunst in Handel und Gewerbe. Original print samples on over 100 historical display boards from the first traveling exhibition Reklame und kaufmännische Drucksachen (Advertisements and Printed Matter for the Salesman) and another traveling exhibition entitled Modernes Buchgewerbe (Modern Book Industry) are on view.

Particularly in printed advertising, a stringent development from Jugendstil to the streamlined typographic concepts by the likes of Lucian Bernhard, Julius Gipkens, Fritz Helmuth Ehmcke, Julius Klinger, and Peter Behrens can be followed. Graphic designer Lucian Bernhard deserves to be highlighted as recognized inventor of the modern German Sachplakat (a streamlined style of poster art focusing on a central object) and man who designed the furnishings for the Deutsche Museum.