The Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge exhibits the estate of the Bauhaus disciple and Werkbund adherent Herbert Hirche.

The exhibition brilliant grey focuses on the specific situation of post-war Germany, in which an ethics of things was proposed as a contribution to material and intellectual reconstruction. Herbert Hirche’s biography made his works ideally suited to resume the morally unencumbered traditions of pre-war modernism, veil the history of the period from 1933 to 1945, and revive the utopian potential of classic Modernism in a reconstructed Germany.

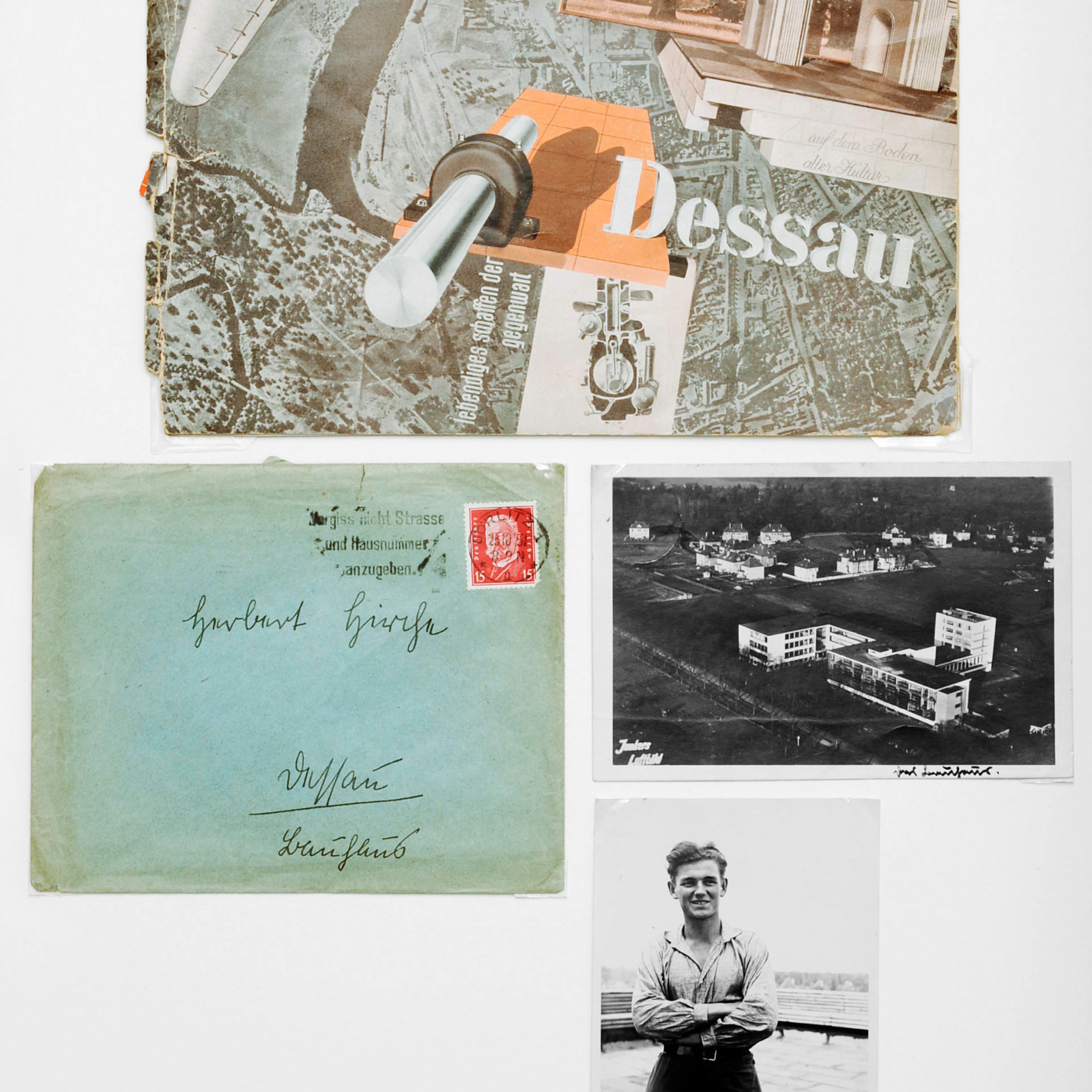

After his apprenticeship and journeyman years as a cabinetmaker, Herbert Hirche began his studies at the Bauhaus in Dessau and Berlin in 1930. When the Bauhaus was closed in 1933, Hirche’s teacher Ludwig Mies van der Rohe put him to work in his studio. Hirche worked for Mies, and for Lilly Reich, until 1938. During the war, Hirche directed building works for the architect Egon Eiermann. After 1945, he worked on planning the reconstruction of Berlin under Hans Scharoun, and joined the Berlin Werkbund group. Many companies associated with the Werkbund produced furniture designed by Hirche, including Wilkhahn, Walter Knoll, Holzäpfel and Wilde+Spieth. Herbert Hirche was also one of the pioneers of the internationally successful designs of Braun appliances. Hirche served many of his patrons as an architect too, building homes, factories and office buildings.

Hirche intended his buildings, interiors and furniture, not to dominate people’s lives, but to afford the greatest possible freedom to their users and occupants. The title of the present exhibition, brilliant grey, is hence a metaphor for the objectivity and neutrality of Hirche’s designs, as well as for their discreet elegance.

In 1957, Hirche’s furniture was found in many apartments in Berlin’s Hansaviertel development as part of the Interbau building exhibition. His unpretentious works were also shown at the Milan Triennale, the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels and the 1964 Documenta, exemplifying the new West German product culture propagated by the Deutsche Werkbund. These objects went abroad as the ambassadors of a young, democratic, better Germany.

After 1945, the Werkbund was chiefly concerned with the reconstruction of cities destroyed by war, the establishment of a contemporary residential style, and the quality of industrial mass production, which was now becoming ubiquitous. Herbert Hirche designed several of the most important exhibitions on these issues, including “Wie wohnen?” in Stuttgart 1949, “Gute Industrieform” in Mannheim 1952; and “Schönheit der Technik” in Stuttgart 1953.

From 1948 on, Herbert Hirche taught at the new College of Applied Arts in the Berlin borough of Weissensee, and in 1952 he accepted a post as Professor of Interior Architecture and Furniture Design at the Stuttgart Academy of Art and Design. Hirche was member of the German Design Council, and as an advisor and mentor he became the éminence grise of the young German Industrial Design Association.

Later, Hirche and his work as an architect and product designer were all but forgotten. Today his simple, utilitarian furniture of the 1950s, created as “silent servants” rather than commercial fetishes, has been reproduced and marketed as “classics” and “iconic designs.” The deep armchair in the entrance installation of the exhibition is an example.

The Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge presents Herbert Hirche with an opportunity to investigate the meaning and the mandate of history. How dim is the past? Does it shine into the present?