According to the reform pedagogy of Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi (1746 – 1827) children would learn best through a direct interaction with their environment and develop language and the faculty of abstraction through this experience.

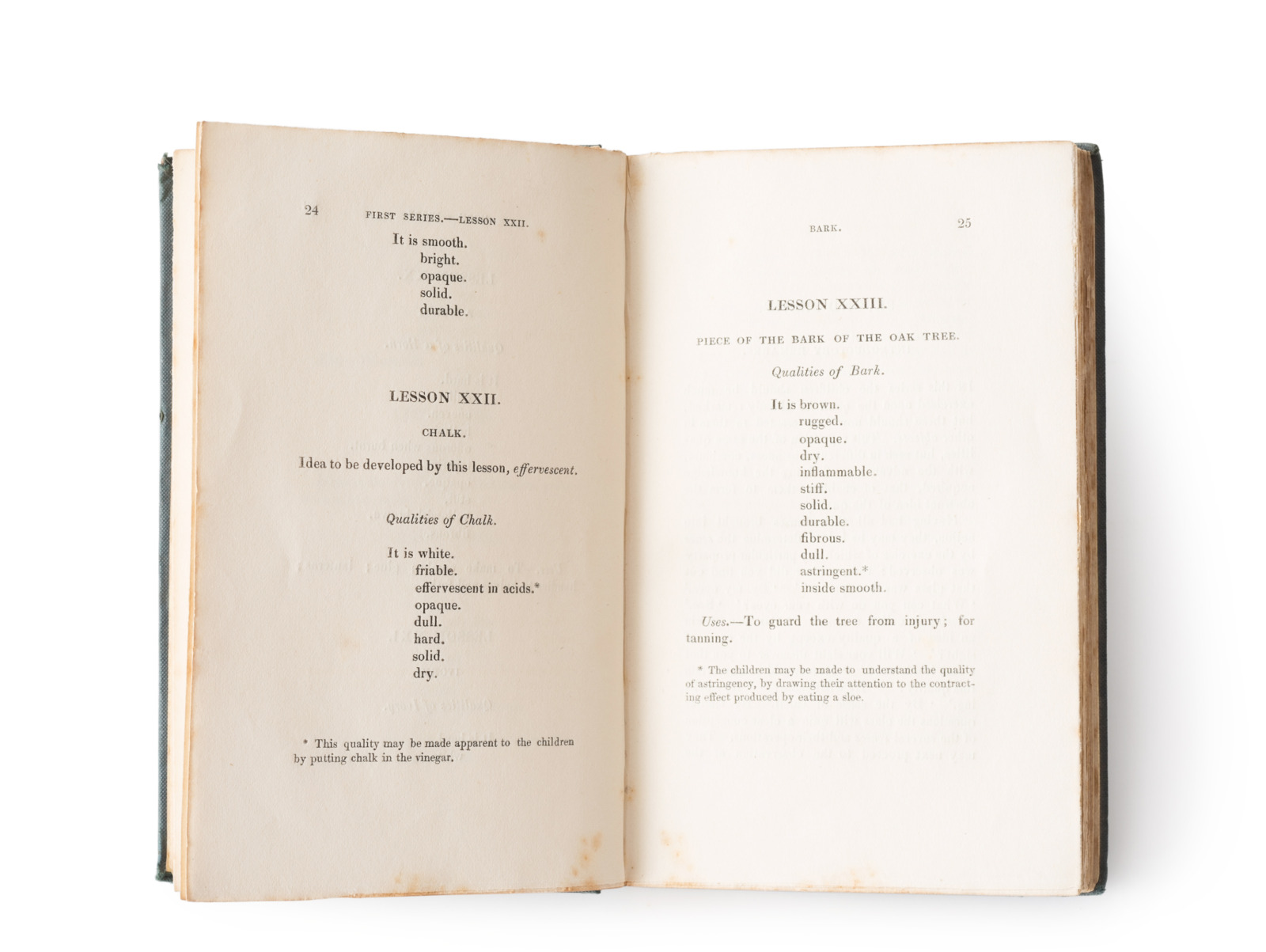

In order to experience this pioneering education method on-site, the Englishman Charles Mayo (1792-1846) spent three years with Pestalozzi in Yverdon. However, he found the teaching practice, which used only things that happened to be at hand, to be chaotic. These shortcomings encouraged him to develop an authoritative and systematic concept with his sister Elizabeth Mayo (1793–1865), resulting in a textbook full of exemplary dialogue and one hundred object descriptions. These should serve as an inspiration for the teachers, because, according to E. Mayo, children would learn better if they described their observations in their own words.

The whole text is structured into five sections, ranging from everyday objects and materials to scientific perspectives. There are minerals, seashells, insects, liquids, spices, paper and fabrics, a pair of scissors and a thimble – the boundaries between natural and artificial, raw and processed are fluent. Often, things are compared to each other to illustrate natural, linguistic or philosophical phenomena. Imported substances like rice, tea and sugar exemplify cultural, geographical and colonial contexts. Between 1830 and 1865, the book was published in more than twenty editions, translated into French and Japanese and was often adapted.

The core of material education is described strikingly by children’s book author John Aikin, whose quotation on the title page of Lessons on Objects reads:

We daily call a great many things by their names without ever inquiring into their nature and properties, so that, in reality, it is only their names, and not the things themselves, with which we are acquainted.